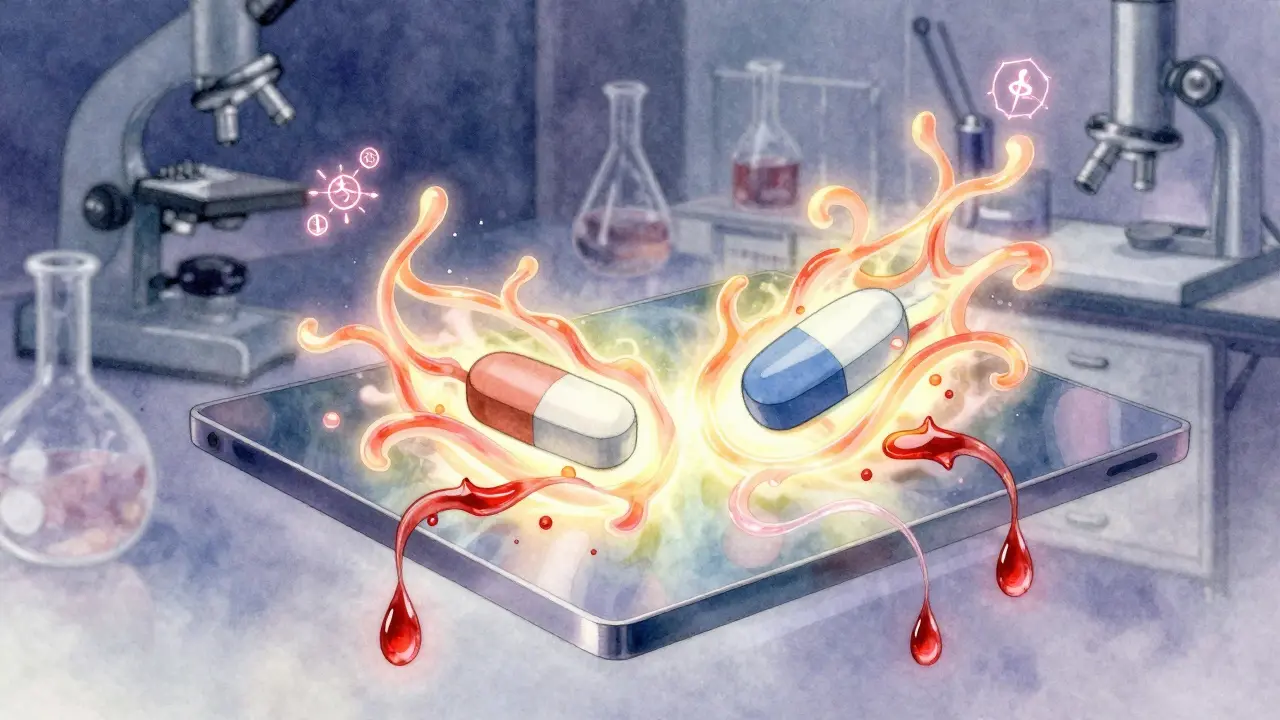

When a patient takes a pill that contains two medicines in one tablet-like a blood pressure drug combined with a diuretic-it’s called a fixed-dose combination (FDC). These aren’t just convenient. They’re critical for managing chronic conditions like HIV, diabetes, and asthma. But getting a generic version of such a product to market isn’t like copying a single-drug pill. The science behind proving it works the same way-called bioequivalence-gets messy fast. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require proof that the generic version delivers the same amount of each active ingredient at the same speed as the brand-name product. Sounds simple. Until you realize the two drugs in the pill might interact with each other, change how they dissolve, or behave differently when delivered through a device like an inhaler or injector.

Why Bioequivalence for Combination Products Is So Hard

For a single-drug tablet, bioequivalence testing is straightforward: give it to 24-36 healthy volunteers, measure blood levels over time, and check if the peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) fall within 80-125% of the brand-name drug. That’s the gold standard. But for a combination product, you’re not just measuring one chemical. You’re measuring two-or sometimes three-active ingredients that may affect each other’s absorption, metabolism, or elimination.

Take a common FDC like amlodipine and atorvastatin. Amlodipine is highly soluble; atorvastatin isn’t. In the tablet, the insoluble drug might clump or bind to the soluble one, changing how quickly it enters the bloodstream. A generic manufacturer can’t just copy the brand’s formula. Even small changes in filler, coating, or manufacturing process can throw off the balance. The FDA now requires generic makers to prove bioequivalence not just to the combination product itself, but also to each individual component taken separately. That means running three-way crossover studies-where volunteers get the brand combo, the brand single drugs, and the generic combo-all in different orders. These studies need 40-60 participants, not 24. And they cost more. Much more.

Topical Products: Measuring What You Can’t See

Imagine a cream for eczema that combines calcipotriene and betamethasone. Both drugs need to penetrate the skin’s outer layer-the stratum corneum-to work. But how do you prove the generic version delivers the same amount? You can’t just take blood samples. The drugs aren’t meant to enter the bloodstream in large amounts. They’re meant to stay in the skin.

The FDA’s current method? Tape-stripping. You press adhesive tape onto the skin 15-20 times, peel it off, and analyze how much drug is in each layer. Sounds crude. It is. And it’s inconsistent. Different labs use different tape types, different pressures, different numbers of strips. One study showed the same cream produced 30% variation in drug measurements just between two labs using the same protocol. In 2022, a generic version of a popular topical FDC failed three times in a row because the bioequivalence results didn’t match across trials. The problem wasn’t the formula-it was the measurement tool. There’s no standard for how deep the tape should go or how much skin to analyze. That’s why many developers are turning to in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) models. These use lab-based skin models to predict how the drug will behave in real skin. Early results show 85% accuracy. But the FDA hasn’t fully accepted them yet.

Drug-Device Combos: It’s Not Just the Medicine

Take an asthma inhaler. The drug is only half the story. The device-the canister, the valve, the mouthpiece-controls how fine the mist is, how much reaches the lungs, and how easy it is for the patient to use. If a generic inhaler looks slightly different, or the button requires a little more force to press, the drug delivery can drop by 20%. That’s enough to make the treatment ineffective.

The FDA requires generic inhalers to match the brand’s aerosol particle size distribution within 80-120%. But measuring that requires expensive equipment and highly trained technicians. And even then, the real test is how the patient uses it. A 2024 FDA workshop found that 65% of complete response letters for generic inhalers cited problems with user interface. That means the patient couldn’t coordinate breathing with pressing the device. A generic might have the exact same chemical formula-but if the timing of the puff is off, the patient gets less medicine. That’s why some developers now run “use error” studies with real patients, not just lab technicians. These cost $500,000 each. And they’re not always required.

Modified-Release Formulations: The High-Stakes Game

Some combination products are designed to release medicine slowly over 12 or 24 hours. Think of a diabetes pill that releases metformin and sitagliptin gradually. If the generic releases the drugs too fast, the patient gets side effects. Too slow, and the drug doesn’t work. The FDA requires tighter bioequivalence limits for these-90-111% instead of 80-125%. That’s a much narrower window.

And it’s not just about the numbers. The release mechanism matters. A generic manufacturer might use a different polymer coating or tablet core. Even if the drug levels in the blood look fine, the release pattern might be wrong. In 2023, the FDA reported that 35-40% of initial ANDA submissions for modified-release FDCs failed bioequivalence testing. Many of these failures happened because the generic released one drug too early and the other too late. The two didn’t stay synchronized. That’s why companies are turning to physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. These computer simulations predict how the drug will behave in the body based on its chemical properties and the formulation. Seventeen generic approvals since 2020 used PBPK models to reduce or replace clinical trials. But not every regulator accepts them yet.

The Cost and Time Burden

Developing a generic single-drug tablet takes 3-5 years and $5-10 million. A combination product? $15-25 million and 5-7 years. Bioequivalence testing alone eats up 30-40% of that budget. Why? Because of the complexity. More volunteers. More samples. More labs. More equipment. A single LC-MS/MS machine-the instrument needed to measure low drug concentrations in blood-costs $400,000. And you need technicians trained for 2-3 years to run it properly.

Topical products are the worst. Clinical endpoint studies for a generic cream can cost $5-10 million per trial and require 200-300 patients. Compare that to a standard bioequivalence study at $1-2 million. Most small generic companies can’t afford it. That’s why the FDA’s Complex Product Consortium was created in 2021. It brings together regulators, manufacturers, and scientists to create product-specific bioequivalence guidelines. So far, they’ve published 12. Companies using them cut development time by 8-12 months. But only a handful of products have these guidelines. The rest? Developers are left guessing.

Regulatory Gaps and Global Inconsistencies

The FDA, EMA, and WHO all want the same thing: safe, effective generics. But they don’t agree on how to get there. The EMA often requires additional clinical trials for combination products that the FDA accepts with bioequivalence data alone. That means a company might spend $20 million to get approval in the U.S., then spend another $3-5 million to re-run studies for Europe. A 2023 study by the European Generic Medicines Association found this duplication adds 15-20% to development costs.

And then there’s the patent problem. Brand companies file dozens of patents around combination products-on the formulation, the device, the method of use. Between 2019 and 2023, legal challenges for drug-device combos rose 300%. One case delayed generic entry for 3.5 years. Even if the science checks out, the legal maze can block access.

What’s Changing-and What’s Next

The FDA is finally recognizing the problem. In 2024, they launched the Bioequivalence Modernization Initiative, aiming to create 50 new product-specific guidances by 2027. The first targets respiratory products-where 78% of submissions fail bioequivalence testing. They’re also working with NIST to develop reference standards for inhalers and topical products. These aren’t just guidelines. They’re physical samples manufacturers can test against. That could reduce lab-to-lab variability.

Meanwhile, PBPK modeling is gaining ground. The FDA has accepted it for 17 complex products. More companies are investing in it. And IVIVC for skin delivery? Pilot data shows it’s reliable. If regulators accept it, we could see clinical trials for topical products cut by half.

The goal isn’t to make testing harder. It’s to make it smarter. Combination products aren’t going away. In fact, they’re growing. In 2023, they made up 38% of the global generic market-$112.7 billion. By 2028, that number could hit $160 billion. But if bioequivalence challenges aren’t solved, 45% of these products may never have a generic alternative. That means patients pay more. Health systems pay more. And innovation slows down.

What Generic Developers Need to Do Now

If you’re developing a generic combination product, don’t wait for perfect guidelines. Start early. Request a Type II meeting with the FDA. Use PBPK modeling to predict outcomes before you run expensive trials. Partner with labs that specialize in complex product testing. And don’t assume what works for a single drug will work for two. The interaction between the drugs is the real challenge-not the drugs themselves.

For regulators, the message is clear: one-size-fits-all bioequivalence doesn’t work anymore. For patients, the stakes are higher than ever. Without better testing methods, the promise of affordable combination therapies-treatments that simplify care and improve adherence-will remain out of reach for millions.

What is bioequivalence for combination products?

Bioequivalence for combination products means proving that a generic version delivers the same amount of each active ingredient at the same rate as the brand-name product. For fixed-dose combinations (FDCs), this requires showing equivalence to both the combined product and the individual drugs taken separately. For drug-device products, it also includes matching delivery performance, like aerosol size or injector force.

Why can’t we just use the same bioequivalence tests as for single drugs?

Single-drug tests measure one active ingredient. Combination products have two or more, and they can interact. One drug might slow down the absorption of another. The formulation might change how each drug dissolves. This means standard two-way crossover studies aren’t enough. You need three-way designs, larger sample sizes, and sometimes multiple analytical methods to track each component.

How do you test bioequivalence for topical combination products?

The FDA currently uses tape-stripping-peeling off 15-20 layers of skin to measure drug content. But this method lacks standardization, leading to high variability between labs. Emerging alternatives include in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) models, which use artificial skin to predict real-world performance. These show 85% accuracy in pilot studies and may replace tape-stripping in the future.

Why do drug-device combination products fail so often?

Even if the drug formula is identical, small differences in the device-like the force needed to press an inhaler or the shape of a nozzle-can change how much medicine reaches the lungs. The FDA requires aerosol particle size to match within 80-120%. But 65% of complete response letters cite user interface issues, meaning patients can’t use the device properly. Testing requires specialized equipment and real-patient use studies, which are expensive and complex.

What’s being done to fix these challenges?

The FDA launched the Bioequivalence Modernization Initiative to create 50 new product-specific guidances by 2027. They’re also developing reference standards with NIST and accepting physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling in 17 approved cases. These tools help predict performance without large clinical trials, reducing cost and time. Industry groups are pushing for global harmonization to avoid duplicate testing across regions.

How do these challenges affect patients?

Delays in generic approval mean patients pay more for combination therapies. In 2020, generic drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion. But if complex products can’t reach the market as generics, that savings disappears. For chronic conditions like asthma or HIV, where patients take multiple pills daily, combination products improve adherence. Without affordable generics, many patients either skip doses or pay out-of-pocket-leading to worse outcomes and higher long-term costs.

Wow. This is one of those posts that makes you realize how much engineering goes into something as simple as a pill. I had no idea that two drugs in one tablet could mess with each other’s absorption like that. The part about amlodipine and atorvastatin? Mind blown. And the tape-stripping method for creams? That’s like science fiction from the 90s. We’re measuring skin layers like it’s a crime scene. Brutal.

Everyone’s overcomplicating this. If the generic has the same chemicals it’s the same drug. End of story. The FDA is just being bureaucratic to protect Big Pharma. All this fancy modeling and 60-person trials? Pure profit protection. People need cheaper meds not PhD-level chemistry lessons.

Kinda fascinating how much of this comes down to measurement tools rather than the drugs themselves. Like the tape-stripping thing. If two labs get 30% different results using the same protocol, then the problem isn’t the generic-it’s the method. We’re trying to measure a fog with a ruler.

The regulatory fragmentation between the FDA and EMA represents a significant inefficiency in global pharmaceutical access. The duplication of clinical trials across jurisdictions imposes unnecessary financial burdens on manufacturers and delays patient access to affordable therapies. Harmonization of bioequivalence standards should be a top priority for international health policy.

Let’s not forget the human side. These aren’t just molecules-they’re lifelines. People with asthma don’t care if the inhaler button needs 10% more force. They just need to breathe. And if the generic works but the patient can’t use it right? That’s not science failure. That’s a design failure. We need to test with real people-not lab rats in white coats.

ok so like… why is this sooo hard?? 😵💫 like i get the drugs interact but why cant we just… i dunno… make the generic match the brand exactly?? like why is it sooo complicated?? 🤯 also who’s paying for all these $500k studies???

It is imperative that regulatory frameworks evolve in tandem with pharmaceutical innovation. The current reliance on outdated methodologies-such as tape-stripping for topical products-is not scientifically robust. The adoption of IVIVC and PBPK modeling, validated through peer-reviewed studies, is not merely advantageous-it is ethically necessary to ensure equitable access to life-saving therapies.

bro… the FDA is just being dramatic. like… a pill is a pill. if it looks the same and has the same ingredients… why are we spending millions on this?? 😭 also… who even uses tape to test skin?? 😅

People think medicine is science but it’s really just corporate theater. You think they care about patients? Nah. They care about patents. They care about lawsuits. They care about keeping prices high so CEOs can buy private islands. This whole bioequivalence mess? It’s a smokescreen. The real drug isn’t in the pill-it’s in the contract.

This is actually really hopeful. I didn’t know PBPK modeling was working so well. If we can cut down trials by half, that’s huge. More generics faster means more people can afford their meds. Small wins matter. Keep pushing for better methods.

Let me be clear-this isn’t about science. It’s about control. The FDA doesn’t want generics to succeed. They’re afraid of losing power. Every delay, every extra test, every ‘requirement’ is a brick in the wall keeping prices high. And the people who suffer? They’re not in the boardrooms. They’re in the parking lots of pharmacies, choosing between insulin and rent.

Let’s be real-America’s healthcare system is broken. We spend more on drugs than any country on earth. But we still can’t get a simple generic inhaler approved because some lab can’t agree on how to peel tape off skin? This isn’t innovation. This is national embarrassment.

One thing I’ve learned working in this space: the biggest barrier isn’t science-it’s communication. If generic manufacturers start early, request FDA Type II meetings, and use PBPK models to guide development, they save millions. It’s not about being smarter-it’s about being strategic. And yeah, the tape-stripping thing is wild. But IVIVC? That’s the future. Let’s not waste time arguing about the past.