DIPF Symptom Assessment Tool

This tool helps identify potential symptoms of drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis. If you experience multiple symptoms, consult your doctor immediately.

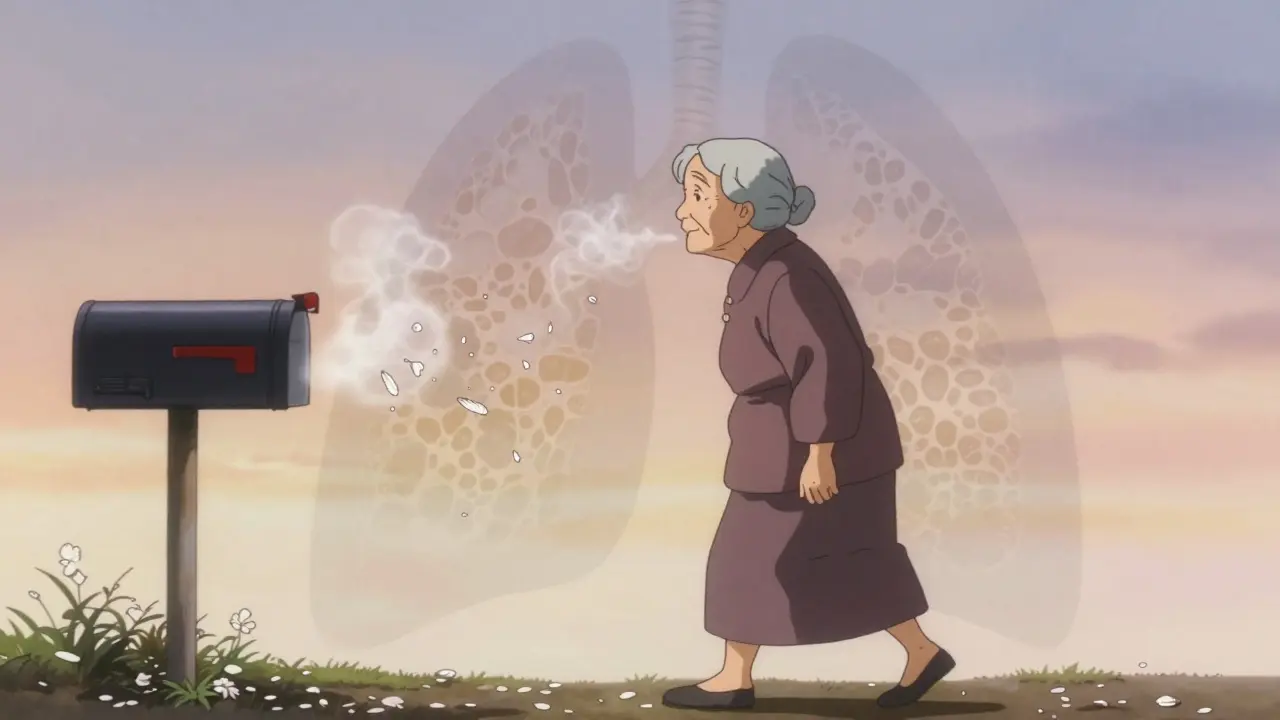

Most people assume that if a drug is approved by health authorities, it’s safe to take. But some medications silently scar your lungs - even if you’ve taken them for years without issue. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis (DIPF) isn’t rare. It’s underdiagnosed, often mistaken for aging, asthma, or a lingering cold. And by the time it’s caught, the damage can be permanent.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis means scar tissue builds up in your lungs. This isn’t like a skin scar - it’s thick, stiff tissue inside the tiny air sacs where oxygen enters your blood. When that happens, your lungs can’t expand properly. Breathing becomes a struggle. You don’t just feel tired - you gasp for air walking up stairs, tying your shoes, or even talking.

DIPF is caused by specific drugs. It’s not an allergic reaction. It’s not dose-dependent. One person takes the same pill for years and stays fine. Another develops lung scarring after just a few months. Why? We don’t fully know. But we do know which drugs are the biggest culprits.

The Top Medications That Can Scar Your Lungs

Over 50 medications have been linked to pulmonary fibrosis. But three stand out in real-world data - nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, and amiodarone. Together, they made up nearly half of all reported cases in New Zealand between 2014 and 2024.

- Nitrofurantoin: Used for urinary tract infections, especially in older women on long-term prevention. It can cause lung damage after 6 months to 10 years. Symptoms often start as a dry cough and get worse slowly. About 47 cases were reported in New Zealand during that time - the most of any drug.

- Methotrexate: Common for rheumatoid arthritis and some cancers. It can trigger acute lung injury within weeks. In one study, 3-7% of arthritis patients on methotrexate developed lung problems. The New Zealand database recorded 45 cases, with some fatal outcomes.

- Amiodarone: A heart rhythm drug. It builds up in your body over time. After taking more than 400 grams total (usually 6-12 months of use), up to 7% of people develop lung scarring. It’s one of the deadliest - 10-20% of severe cases end in death, even after stopping the drug.

Chemotherapy drugs are another major group. Bleomycin - used for testicular cancer and lymphoma - causes lung toxicity in up to 20% of patients. Cyclophosphamide and other chemo agents carry similar risks. Even newer cancer immunotherapies, like pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have been linked to sudden, severe lung inflammation since their rollout in 2011.

Other offenders include penicillamine (for rheumatoid arthritis), gold salts, sulfonamides, and some antibiotics. The list keeps growing as new drugs hit the market.

Why Does This Happen? The Hidden Mechanism

It’s not just one pathway. Different drugs damage the lungs in different ways. Some trigger oxidative stress - like a chemical fire inside lung cells. Others cause immune cells to attack lung tissue by mistake. Some drugs break down into toxic byproducts that settle in the lungs over time.

Amiodarone, for example, accumulates in lung fat. Over months, it disrupts cell membranes and causes inflammation that turns into fibrosis. Nitrofurantoin generates free radicals that damage the delicate lining of air sacs. Methotrexate interferes with cell repair, making it harder for lungs to heal after minor injuries.

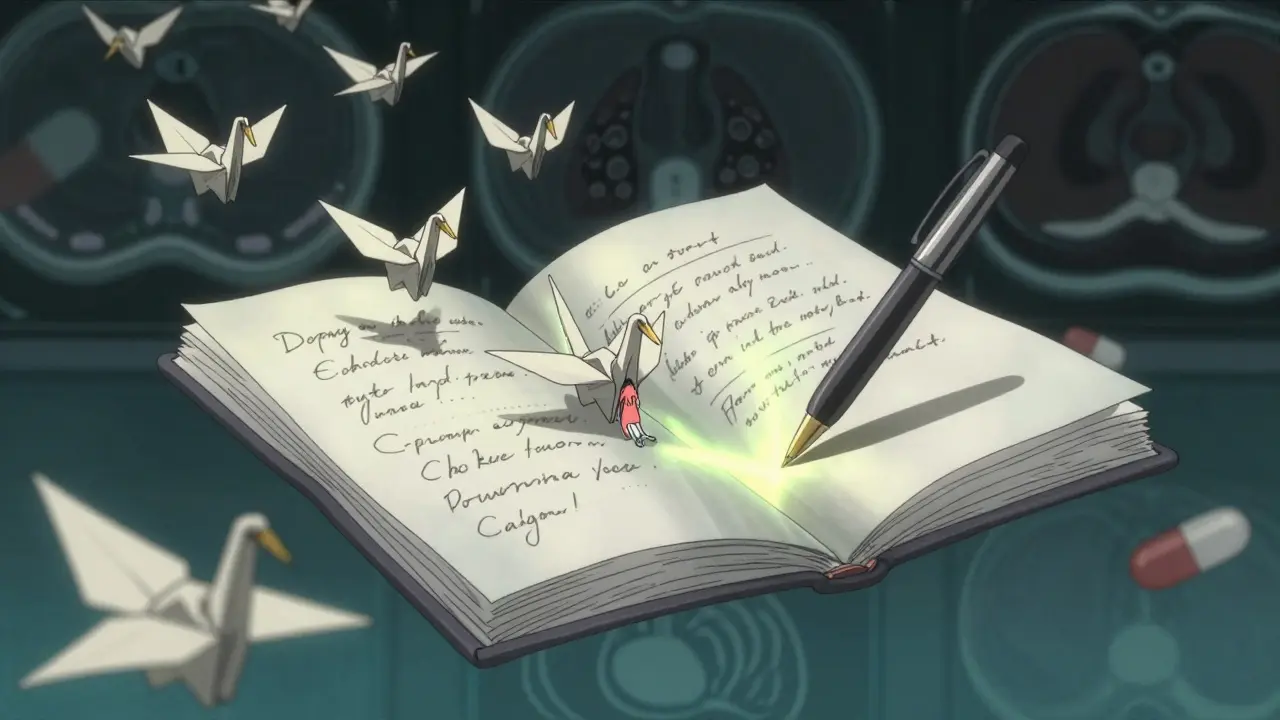

And here’s the kicker: there’s no single test to confirm DIPF. No blood marker. No unique scan pattern. Diagnosis is a process of elimination. Your doctor must rule out infections, autoimmune diseases, asbestos exposure, and other lung conditions - all while digging into your full medication history.

What Do the Symptoms Look Like?

Early signs are easy to ignore:

- A dry, persistent cough - not from a cold, not from allergies. Just won’t go away.

- Shortness of breath during light activity - climbing stairs, walking to the mailbox, carrying groceries.

- Fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest.

- Unexplained weight loss or low-grade fevers.

- Chest discomfort or aching.

According to patient surveys, 78% report worsening breathlessness. 65% have a chronic cough. About one-third also get joint pain and fevers. These symptoms don’t come on suddenly. They creep in over weeks or months. Many patients are told they’re just getting older. Or they have COPD. Or it’s just asthma. The average time from first symptom to correct diagnosis? Over 8 weeks.

How Is It Diagnosed?

If your doctor suspects DIPF, they’ll start with a high-resolution CT scan of your chest. It shows the telltale patterns of scarring - honeycombing, reticulation, ground-glass opacities. But these patterns aren’t unique to drug-induced cases. That’s why your medication history matters more than the scan.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) measure how well your lungs work. A drop in diffusion capacity (DLCO) is often the earliest sign. It means oxygen isn’t moving properly from your lungs into your blood.

Bronchoscopy or lung biopsy might be needed if the diagnosis is unclear. But many doctors skip these if the clinical picture and drug history are strong enough. The key question: Could this drug be doing this? If yes - and no other cause fits - DIPF is likely.

What Happens If You Stop the Drug?

This is the most critical point: Stopping the drug is the single most effective treatment. In 89% of cases, lung function improves within 3 months after discontinuation.

But stopping alone isn’t always enough. If inflammation is still active, doctors prescribe high-dose corticosteroids like prednisone - usually 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight daily. That’s a strong dose, often 40-60 mg per day. It’s tapered slowly over 3 to 6 months to avoid rebound inflammation.

Oxygen therapy is added if blood oxygen levels fall below 88% at rest. Some patients need it long-term. Others wean off as their lungs heal.

Recovery isn’t guaranteed. About 15-25% of patients end up with permanent lung damage - even after stopping the drug. The earlier you catch it, the better your odds. If caught early, 75-85% of people make a good recovery.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

You’re more likely to develop DIPF if you:

- Are over 60 years old

- Have pre-existing lung disease (like COPD or prior pneumonia)

- Take multiple high-risk drugs at once

- Have been on the drug for more than 6 months

- Have a history of smoking

Women are more likely to be prescribed nitrofurantoin for UTIs. Older adults are more likely to get amiodarone for heart rhythm issues. Rheumatoid arthritis patients on methotrexate are a known high-risk group. But again - it’s unpredictable. Some 75-year-olds take amiodarone for 10 years with no issues. Others develop fibrosis after 8 months.

What Can You Do to Protect Yourself?

If you’re on any of these drugs, here’s what you need to know:

- Know the warning signs. A dry cough or breathlessness that won’t go away? Don’t brush it off.

- Ask your doctor. Before starting any new medication, ask: “Can this affect my lungs?” If they say no, ask for the evidence.

- Get baseline lung tests. If you’re starting amiodarone, methotrexate, or bleomycin, ask for a pulmonary function test and chest X-ray before you begin. Repeat every 6-12 months.

- Report symptoms immediately. Don’t wait. If you develop a new cough or shortness of breath, see your doctor within days - not weeks.

- Keep a medication list. Include dosages and start dates. Bring it to every appointment.

Healthcare providers are still falling behind. A 2022 survey found only 58% of primary care doctors routinely screen for lung symptoms in patients on high-risk drugs. That’s not good enough.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Is Getting Worse

Between 2014 and 2024, reported cases of drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis rose by 23.7%. Why? Two reasons:

- More people are taking high-risk drugs - especially older adults with multiple chronic conditions.

- More cases are being recognized. Doctors are learning. Pharmacovigilance systems are improving.

But new drugs are coming out faster than we can study their long-term effects. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, targeted cancer therapies, biologics for autoimmune disease - these are powerful, but their lung risks are still being mapped.

Researchers are now looking for genetic markers that predict who’s at risk. The goal? A simple blood test before prescribing - so you don’t have to wait for symptoms to appear.

Final Thoughts: Awareness Saves Lungs

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis isn’t a death sentence. But it’s not harmless, either. It’s a silent threat hiding in plain sight - in your medicine cabinet, in your doctor’s prescription pad, in the quiet cough you’ve been ignoring.

If you’re on one of these drugs, don’t panic. But don’t ignore your body, either. Talk to your doctor. Get tested. Know the signs. Catch it early, and your lungs might still heal. Wait too long, and the scars stay forever.

Medications save lives. But they can also scar them. The difference? Awareness - and action.

This is why I stopped trusting Big Pharma the second I saw how many drugs have hidden landmines. They get approved because some lab rat in a cage didn’t drop dead on day one. Meanwhile, grandma’s taking nitrofurantoin for 8 years and suddenly can’t breathe walking to the bathroom. Who’s accountable? No one. They just slap on a tiny warning in the 12-point font no one reads.

The data on nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, and amiodarone is compelling, especially the 47, 45, and cumulative 7% risk figures. The pathophysiological mechanisms-oxidative stress, immune dysregulation, and toxic metabolite accumulation-are well-documented in pulmonary toxicology literature. However, the absence of a definitive biomarker remains a critical diagnostic gap. Future research should prioritize proteomic or transcriptomic signatures to enable early detection.

My uncle took amiodarone for 5 years. One day he couldn’t climb the stairs. Doctors thought it was his heart. Turned out his lungs were basically cement. He’s on oxygen now. Don’t ignore a cough. Just because you’re old doesn’t mean you’re supposed to feel like you’re breathing through a straw.

YOU ARE NOT TOO OLD TO BREATHE EASILY. If you’re wheezing walking to the fridge, it’s not ‘just aging.’ It’s your body screaming. Ask your doc. Get tested. Your lungs didn’t sign up for this. Fight for them. 💪❤️

Oh wow, a 2024 article that actually mentions pharmacovigilance. How quaint. Did you also learn that water is wet and gravity exists? I’m sure the FDA will now implement mandatory lung scans before prescribing anything that isn’t aspirin. 🙄

I’ve been on methotrexate for 6 years for RA. Never had symptoms. But now I’m wondering-should I get a PFT just in case? I don’t want to wait until I’m gasping. But I also don’t want to freak out over nothing.

The 89% improvement rate post-discontinuation is statistically significant, but the confounding variables-concurrent corticosteroid use, baseline DLCO, and comorbidities-are rarely controlled in retrospective cohorts. The real clinical utility lies in stratifying risk via genetic polymorphisms (e.g., GSTP1, SOD2), which remain underexplored in current guidelines.

Thank you for sharing this. I never realized how many common meds could quietly damage our lungs. I’ve been meaning to talk to my doctor about my amiodarone. I’ll schedule an appointment this week. It’s never too late to be careful. 🙏

This is an exceptionally well-researched and clinically relevant summary. The emphasis on early detection, baseline pulmonary function testing, and patient-driven advocacy aligns with current best practices in preventive pulmonology. I strongly encourage all clinicians to integrate these screening protocols into routine care for high-risk pharmacotherapy regimens.

My mom got nitrofurantoin for a UTI. She’s 72. Coughed for 3 months. They said it was allergies. Then she collapsed. Now she’s on oxygen. Don’t let this happen to your grandma. 🙏😭

Thank you for this. I work in a clinic and we don’t screen for this nearly enough. I’m printing this out and putting it on the wall next to the prescription station. Awareness starts with us.