For decades, cancer treatment meant chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery - harsh, broad-stroke approaches that damaged healthy cells along with tumors. But since 2011, a quiet revolution has been underway. Checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cell therapy are not just new drugs or procedures. They’re fundamentally changing how the body fights cancer - by turning the patient’s own immune system into a precision weapon.

How Checkpoint Inhibitors Unleash the Immune System

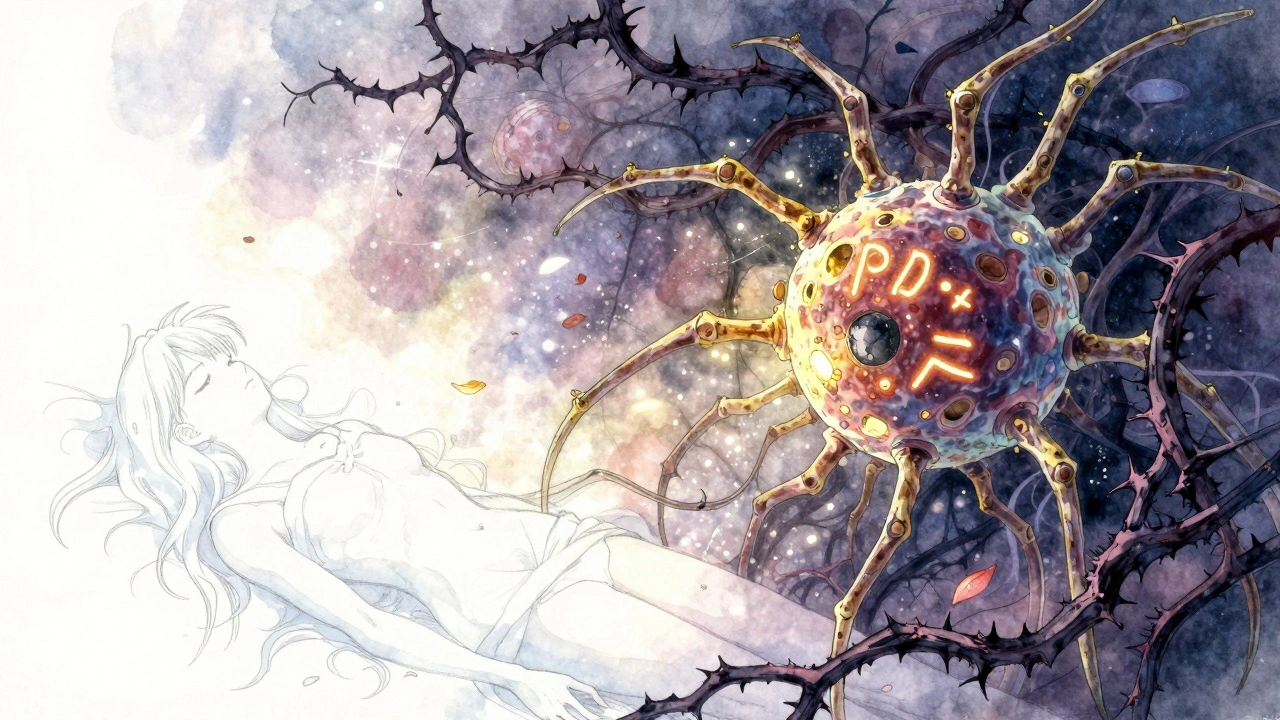

Your immune system is always watching for trouble. T cells, the body’s frontline soldiers, are trained to recognize and kill abnormal cells - including cancer. But cancer cells are sneaky. They learn to hide by activating natural brakes on the immune system, called checkpoints. Two of the most important are PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4. When these checkpoints are turned on, T cells stand down, even when they’re right next to a tumor.

Checkpoint inhibitors are monoclonal antibodies designed to block those brakes. Drugs like pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) target PD-1. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) blocks CTLA-4. By doing this, they don’t attack cancer directly. Instead, they remove the signal telling T cells to stand down. The result? T cells wake up, recognize the tumor, and start killing it.

This approach works best in cancers with high mutation rates - like melanoma, lung cancer, and kidney cancer - where the tumor looks more “foreign” to the immune system. Response rates vary: about 20-40% of patients see meaningful shrinkage. But for those who respond, the results can last for years. Some patients with advanced melanoma have lived more than a decade after starting treatment.

CAR-T Therapy: Engineering Your Own Cancer-Fighting Cells

If checkpoint inhibitors are about removing barriers, CAR-T therapy is about building a better army. CAR-T stands for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Here’s how it works:

- A patient’s blood is drawn, and T cells are separated out.

- In a lab, those T cells are genetically modified with a virus to express a synthetic receptor - the CAR - that’s designed to latch onto a specific protein on cancer cells, like CD19 on B cells.

- The modified cells are grown in large numbers - sometimes hundreds of millions.

- The patient receives chemotherapy to clear space in the immune system.

- The engineered CAR-T cells are infused back into the patient.

Once inside, these supercharged T cells hunt down cancer cells with laser focus. In relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), CAR-T therapy achieves complete remission in 60-90% of children and young adults. That’s unprecedented.

But it’s not magic. CAR-T therapy only works well for certain blood cancers - leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma - where the target antigen (like CD19 or BCMA) is found almost exclusively on cancer cells. In solid tumors - lung, breast, colon - it’s been far less effective. Why? The tumor environment is hostile. It’s full of suppressive signals, physical barriers, and immune-evasive tricks that shut down even the most engineered T cells.

Side Effects: Power Comes With Risk

Both therapies can cause serious side effects - but they’re very different.

Checkpoint inhibitors trigger immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Since the immune system is no longer restrained, it can attack healthy organs. Common issues include colitis (inflammation of the colon), skin rashes, thyroid dysfunction, and pneumonitis (lung inflammation). About 30-40% of patients get a rash. Up to 15% develop colitis. These are manageable with steroids if caught early, but they can be life-threatening if ignored.

CAR-T therapy brings its own dangers. The biggest is cytokine release syndrome (CRS). When millions of engineered T cells activate at once, they flood the body with inflammatory signals. Symptoms: high fever, low blood pressure, trouble breathing. In 50-70% of patients, CRS occurs. Severe cases need intensive care. Another risk is immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), which causes confusion, seizures, or speech problems in 20-40% of patients. Both CRS and ICANS usually appear within days of infusion.

There’s also “on-target, off-tumor” toxicity. If the CAR-T cell targets an antigen that’s also present on healthy cells, it can destroy them. For example, targeting CD19 wipes out not just cancerous B cells, but all B cells - meaning patients need lifelong antibody replacement therapy.

Combining the Two: The Next Frontier

Neither therapy alone is enough for most solid tumors. But what if you combine them?

Researchers are now engineering CAR-T cells that don’t just hunt cancer - they also fight the tumor’s defenses. One breakthrough: CAR-T cells modified to secrete their own PD-1-blocking antibodies right inside the tumor. This local delivery means the checkpoint inhibitor hits the cancer hard, but doesn’t flood the whole body. In mouse studies, this cut immune pneumonitis by 42% while boosting tumor killing.

Other tricks include arming CAR-T cells with IL-12 to make them more aggressive, or blocking PTP1B - an internal checkpoint that slows T cells down. One study showed blocking PTP1B tripled the number of T cells that reached breast tumors.

As of early 2024, over 47 clinical trials are testing CAR-T plus checkpoint inhibitors together. Two-thirds of them focus on solid tumors - pancreatic, ovarian, glioblastoma. Early results are mixed, but the logic is solid: CAR-T brings the soldiers. Checkpoint inhibitors keep them fighting.

Access, Cost, and the Real-World Gap

These therapies are expensive and complex. A single CAR-T treatment costs between $373,000 and $475,000. The manufacturing process takes 3-5 weeks. Only specialized centers - mostly academic hospitals - can handle it. In the U.S., 87% of CAR-T treatments happen at just 15% of cancer centers.

And access isn’t equal. Studies show Black patients are 31% less likely to get CAR-T therapy than White patients. Medicaid patients are 23% less likely to receive checkpoint inhibitors. The reasons? Insurance hurdles, lack of specialist referrals, transportation, and systemic bias.

Checkpoint inhibitors are easier to get. They’re “off-the-shelf” - just like any other drug. But even then, cost and prior authorization delays can push patients out of care.

What’s Next?

The future is in smarter, safer, and more widely available versions.

- Off-the-shelf CAR-T: Using donor T cells instead of the patient’s own. This cuts wait time from weeks to days.

- New targets: Beyond CD19 and BCMA, researchers are hunting for antigens unique to solid tumors.

- Armored CAR-T: Cells engineered to release growth factors or block suppressive signals like TGF-beta.

- Biomarkers: Finding which patients will respond before treatment starts - so no one gets a $500,000 therapy that won’t work.

The goal isn’t just to extend life by months. It’s to make cancer a chronic, manageable condition - or even cure it.

For patients who’ve run out of options, these therapies are more than science. They’re a second chance.

How do checkpoint inhibitors differ from CAR-T therapy?

Checkpoint inhibitors are intravenous drugs that block signals cancer uses to hide from the immune system. They work systemically and are used for many cancer types. CAR-T therapy is a personalized treatment where a patient’s own T cells are genetically modified to target cancer, then reinfused. It’s highly specific, mostly used for blood cancers, and requires complex manufacturing.

Can checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T therapy be used together?

Yes, and this is one of the most promising areas in cancer research. Combining them helps overcome the limitations of each. CAR-T cells bring immune cells into the tumor, while checkpoint inhibitors prevent those cells from being shut down. Early trials show better tumor control, especially in solid cancers where neither works well alone.

Why doesn’t CAR-T therapy work well for solid tumors?

Solid tumors create a hostile environment. They block T-cell entry, release chemicals that suppress immune activity, and often lack clear, unique targets. CAR-T cells can’t survive or function well in this setting. New versions are being designed to resist suppression, secrete their own immune boosters, and target better antigens.

What are the biggest side effects of CAR-T therapy?

The two most serious are cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). CRS causes high fever, low blood pressure, and breathing problems. ICANS affects the brain, leading to confusion, seizures, or trouble speaking. Both require immediate medical care and are most common in the first two weeks after infusion.

Is immunotherapy better than chemotherapy?

It’s not better - it’s different. Chemotherapy kills fast-growing cells, both cancerous and healthy. Immunotherapy trains the body to fight cancer specifically. For some patients, immunotherapy offers longer-lasting results with fewer long-term side effects. But it doesn’t work for everyone. The choice depends on cancer type, stage, biomarkers, and patient health.

How long does CAR-T therapy take from start to finish?

The entire process takes 4 to 6 weeks. First, T cells are collected (1-2 days). Then they’re sent to a lab for genetic modification and growth - this takes 3-5 weeks. Meanwhile, the patient gets chemotherapy to prepare their immune system. Once the cells are ready, they’re infused in a single day. Recovery takes weeks to months, with close monitoring for side effects.

Are there alternatives to CAR-T therapy for blood cancers?

Yes. For some patients, stem cell transplants or newer antibody-based drugs like bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) are options. But CAR-T has shown superior long-term remission rates in relapsed or refractory cases. For patients who’ve failed other treatments, CAR-T is often the most effective choice.

This is wild. I had no idea our own immune system could be turned into a precision weapon. My uncle got Keytruda last year and he's been in remission for 18 months now. Like, no chemo, no hair loss, just... living. 🙌

i read this whole thing and cried a little. my mom had melanoma and they tried everything. if this had been available 5 years ago... i dont even know. thank you for writing this.

Look, I get that this sounds like science fiction, but let’s be real - we’re talking about a multi-billion dollar industry that’s been pushing these therapies as miracle cures while the real issue is systemic healthcare inequality. The fact that Black patients are 31% less likely to get CAR-T isn’t a bug, it’s a feature of a broken system. And don’t get me started on how these treatments are marketed as ‘personalized medicine’ when they’re only accessible to the wealthy who can navigate the insurance maze. This isn’t progress - it’s privilege with a lab coat.

Honestly, if you’re still comparing immunotherapy to chemotherapy, you’re operating on 2010-era knowledge. Chemo is the equivalent of using a flamethrower to kill a mosquito. Checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T are surgical strikes. The fact that you’re even asking if it’s ‘better’ shows a fundamental misunderstanding of oncology’s paradigm shift. This isn’t evolution - it’s revolution.

While the scientific advancements presented herein are undeniably laudable, one must not overlook the ethical imperative to interrogate the commodification of human biology. The transformation of T-cells into proprietary, patent-encumbered biologics represents a profound ontological rupture - wherein the body, once a site of natural resilience, is now a factory for corporate profit. One must ask: at what cost does our salvation come?

This is the future. No fluff. No hype. Just science that works. If you're a patient or a caregiver, this is hope with data behind it. Keep pushing for access. Keep demanding equity. We owe it to every person who's been told there's nothing left.

I work in oncology nursing and let me tell you - the day we gave CAR-T to a 7-year-old with relapsed ALL and she started drawing rainbows again? That’s the kind of magic no chemo ever gave us. Yeah, CRS is scary. Yeah, it’s expensive. But watching a kid eat ice cream for the first time in a year? Worth every penny.

For anyone new to this - don’t get discouraged by the cost or complexity. There are patient advocacy groups, nonprofit programs, and hospital financial aid teams that can help. I’ve seen families go from despair to remission because someone took the time to guide them. You’re not alone. Reach out. Ask for help. We’re all in this together.

I’m Nigerian-American and I’ve seen how this tech skips over communities like mine. But I also know what’s possible. My cousin in Lagos got access through a trial in South Africa - same protocol, same results. This isn’t just an American problem. It’s a global one. We need to push for decentralized manufacturing, open-source protocols, and global equity. This isn’t charity - it’s justice.

The fundamental tension here lies in the ontological reconfiguration of the self through bioengineering. CAR-T doesn't merely treat cancer - it reconstitutes the immunological subjectivity of the patient. The CAR receptor becomes an exoskeleton of agency, an artificial limb of immune cognition. We are no longer treating disease; we are rewriting the biological narrative of survival. The tumor microenvironment, once a fortress, is now a contested semiotic field where cytokines speak in dialects of inflammation and suppression. This is not medicine - it is post-human phenomenology.

I’m not saying immunotherapy is bad. But you people act like it’s the Second Coming. My cousin got it. Got CRS. Ended up in the ICU for 3 weeks. Lost her hair anyway. Spent $400K. And still didn’t live past 2 years. Meanwhile, the pharma execs are on their yachts. So yeah, it’s ‘revolutionary’ - just not for the people who actually pay for it.