Imagine taking more opioids to ease your pain-only for it to get worse. This isn’t a rare mistake. It’s opioid-induced hyperalgesia, a real and often misunderstood condition where the very drugs meant to reduce pain actually make you more sensitive to it. You’re not imagining it. Your body has changed in ways that aren’t always obvious, and the solution isn’t more pills-it’s a smarter approach.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) happens when long-term opioid use flips a switch in your nervous system. Instead of blocking pain signals, opioids start amplifying them. This isn’t tolerance-that’s when you need higher doses to get the same effect. With OIH, higher doses make your pain broader, sharper, and more intense. You might feel pain in places you never did before, or even hurt from light touches-a condition called allodynia.

It’s not just a theory. First seen in lab rats in 1971, OIH has since been confirmed in thousands of human cases. Around 2% to 15% of people on long-term opioids develop it, and some experts believe up to 30% of cases labeled as "tolerance" are actually OIH. The problem? Most doctors don’t test for it. They see rising pain and assume the disease is getting worse. So they prescribe more opioids. And the cycle gets worse.

How Do You Know It’s OIH and Not Something Else?

Distinguishing OIH from other issues is tricky, but there are clear red flags:

- Your pain spreads beyond its original location-like back pain now radiating to your legs, arms, or even your head.

- You’re on higher doses, but the pain keeps getting worse, not better.

- You start feeling pain from things that never hurt before-like clothing brushing your skin or a light poke.

- Your pain doesn’t match your diagnosis. For example, you have osteoarthritis, but now your whole body aches.

- Your pain flares up even when you’re not moving or under physical stress.

Unlike withdrawal, OIH doesn’t come with sweating, nausea, or anxiety. Unlike disease progression, imaging scans won’t show new damage. The key clue? Pain gets worse when you increase the opioid dose. That’s the opposite of what should happen.

Doctors can use a tool called the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ), which has been shown to catch OIH in 85% of cases. It asks simple questions about pain patterns and how they respond to medication changes. But many clinics still don’t use it-so if you suspect OIH, you may need to bring it up yourself.

Why Does This Happen? The Science Behind the Pain

It’s not just "your body got used to it." OIH is a complex neurobiological shift. Here’s what’s happening inside your nervous system:

- NMDA receptor activation: Opioids trigger NMDA receptors in your spinal cord and brain-receptors normally involved in learning and pain memory. When overstimulated, they turn up the volume on pain signals.

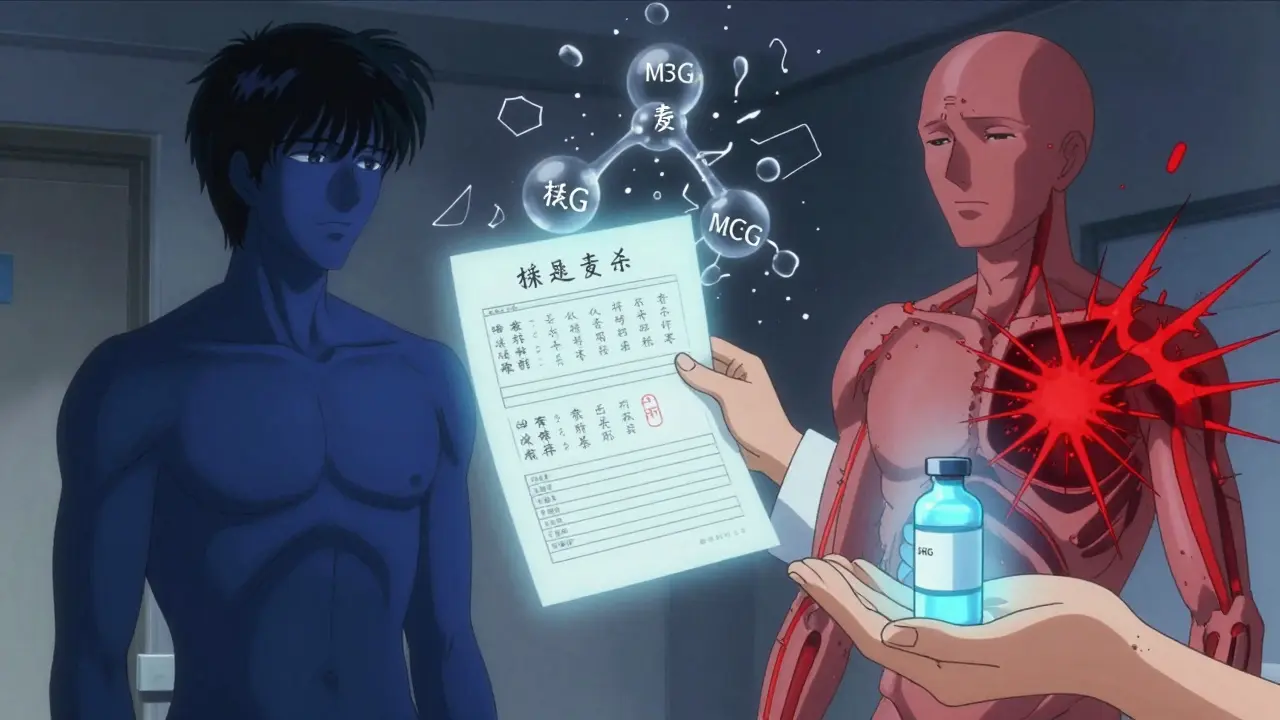

- Toxic metabolites: Some opioids, like morphine and hydromorphone, break down into substances like M3G (morphine-3-glucuronide). These don’t help with pain-they irritate nerve cells and make you more sensitive.

- Dynorphin surge: Your body releases more dynorphin, a natural chemical that, in excess, promotes pain instead of blocking it.

- Genetic factors: People with certain variations in the COMT gene (which affects how your body handles stress chemicals) are more likely to develop OIH.

- Descending facilitation: Your brain starts sending more "pain go" signals down the spine instead of "pain stop" ones.

This is why ketamine-a drug that blocks NMDA receptors-works so well for OIH. It doesn’t just mask pain; it resets the system. The same goes for gabapentin and clonidine, which calm overactive nerve pathways.

Who’s Most at Risk?

OIH doesn’t hit everyone. Certain factors make it more likely:

- High-dose opioids-especially over 300 mg of morphine per day or equivalent.

- Long-term use-usually after 2 to 8 weeks of daily use.

- Renal problems-your kidneys can’t clear opioid byproducts, so they build up and worsen sensitivity.

- History of chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia or neuropathy.

- Genetic predisposition-COMT gene variants are a known risk factor.

People with cancer-related pain or post-surgical pain on IV opioids are especially vulnerable. But even those on oral prescriptions for back pain or arthritis can develop it. It’s not about addiction-it’s about biology.

How Is OIH Treated? The Right Way Forward

More opioids will not fix this. In fact, they’ll make it worse. The goal is to reverse the sensitization. Here’s what works:

1. Taper the Opioid Dose

Reducing your dose by 10% to 25% every 2 to 3 days is the most common and effective first step. It sounds scary-but studies show pain improves in most patients within 2 to 4 weeks. Complete resolution often takes 4 to 8 weeks. You won’t feel better overnight, but you’ll notice the sharp edges of your pain softening.

2. Switch Opioids

Not all opioids are the same. Methadone is often chosen because it blocks NMDA receptors, just like ketamine. Buprenorphine is another good option-it has a ceiling effect that reduces the risk of overstimulating pain pathways. Avoid switching to another high-dose morphine or hydromorphone product. You’ll just repeat the problem.

3. Add NMDA Antagonists

Ketamine infusions (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour) can rapidly reverse OIH. Many pain clinics now offer low-dose ketamine as a targeted treatment. Oral NMDA blockers like dextromethorphan are less effective but may help in milder cases.

4. Use Gabapentinoids or Alpha-2 Agonists

Gabapentin (300-1800 mg daily, split into three doses) and pregabalin calm overactive nerves. Clonidine (0.1-0.3 mg twice daily) reduces central nervous system hyperactivity. Both are well-tolerated and often used together with opioid reduction.

5. Add Non-Drug Therapies

Physical therapy helps retrain movement patterns and reduce fear of pain. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses the emotional loop that makes pain feel worse. Mindfulness and graded activity programs have shown strong results in reducing pain sensitivity over time.

What If You’re Scared to Reduce Your Opioids?

Many patients resist lowering their dose because they fear the pain will explode. That’s understandable. But here’s the truth: the pain you’re feeling right now is partly caused by the opioid. Reducing it doesn’t mean going back to square one-it means removing a trigger.

Studies show that 40% to 60% of patients initially refuse to taper. But among those who do, 70% report better pain control and improved quality of life within two months. Work with a pain specialist who understands OIH. Don’t try to do it alone. A slow, supported taper with backup medications makes all the difference.

What’s New in OIH Research?

OIH is no longer ignored. In 2024, the FDA updated opioid labels to include warnings about hyperalgesia. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) now has 3 full pages of guidelines on recognizing and treating it. Pain fellowship programs jumped from 30% teaching OIH in 2010 to 78% in 2023.

Research is moving fast. A major NIH study (NCT05217891) is tracking genetic markers linked to OIH risk and should finish in 2026. Two commercial genetic tests for COMT variants are expected to launch in mid-2025. These could help doctors predict who’s at risk before starting opioids.

Pharmaceutical companies are investing heavily-OIH-specific drug development funding rose 27% in 2023. Three new NMDA modulators are now in Phase II/III trials. This isn’t just about better painkillers-it’s about rethinking how we treat pain altogether.

Final Thoughts: It’s Not Weakness. It’s Biology.

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia isn’t a failure of willpower. It’s not addiction. It’s a biological response to prolonged opioid exposure-like how your skin burns after too much sun. You didn’t do anything wrong. But now you need a different kind of care.

If you’ve been on opioids for months or years and your pain keeps climbing, ask your doctor: "Could this be OIH?" Bring the facts. Mention the OIHQ. Ask about ketamine, methadone, or gabapentin. Don’t accept more pills as the only answer. You deserve a treatment plan that fixes the problem-not makes it worse.

The future of pain management isn’t just about stronger drugs. It’s about smarter ones-and knowing when to stop.

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia be reversed?

Yes, OIH can be reversed. The most effective approach is reducing or switching opioids, often combined with medications like ketamine, gabapentin, or clonidine. Most patients see improvement within 2 to 4 weeks, with full recovery taking 4 to 8 weeks. The key is stopping the cycle of dose escalation.

Is OIH the same as opioid tolerance?

No. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. OIH means your pain gets worse with higher doses. Tolerance is about reduced drug effect; OIH is about increased pain sensitivity. They can happen together, but they require different treatments.

Does everyone on opioids get OIH?

No. Only about 2% to 15% of long-term opioid users develop OIH. Risk increases with high doses, long duration, kidney problems, and certain genetic factors. It’s not inevitable, but it’s common enough to be screened for in chronic pain patients.

Can I still use opioids after having OIH?

It’s possible, but risky. If opioids are absolutely necessary, switching to a different type like buprenorphine or methadone-both with NMDA-blocking properties-is safer. Low doses, short duration, and close monitoring are essential. Many patients choose to avoid opioids entirely after experiencing OIH.

How long does it take to recover from OIH?

Most people start feeling better within 2 to 4 weeks of reducing their opioid dose. Complete resolution of symptoms usually takes 4 to 8 weeks. Recovery is slower if you’ve been on very high doses for over a year. Adding non-drug therapies like physical therapy and CBT can speed up the process.

Are there tests to diagnose OIH?

There’s no single blood test, but the Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia Questionnaire (OIHQ) is validated and used in clinics with 85% accuracy. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) can measure pain thresholds before and after opioid use-patients with OIH show lower thresholds (more sensitivity). Diagnosis is mostly clinical, based on symptom patterns and response to dose changes.

Can OIH happen with low-dose opioids?

Yes, though it’s less common. OIH is more likely with high doses, but cases have been reported even with low-dose, long-term use-especially in people with genetic risks or existing nerve sensitivity. Duration matters as much as dose. If you’ve been on opioids for over 6 months, even at low doses, OIH should be considered.

Man, I never realized opioids could make pain worse. I thought it was just about addiction. This article opened my eyes. I’ve got a cousin on long-term meds for back pain-gotta send this to her.

It’s wild how our bodies turn against us when we try to fix things. OIH feels like the universe’s ironic joke-painkillers becoming pain amplifiers. We need way more awareness around this. Not everyone’s weak. Some of us are just biologically misaligned.

If you’re reading this and scared to taper-don’t panic. I did it. Took 6 weeks. Felt like dying for the first two, but then? The sharp edges softened. Now I sleep. I walk. I breathe. You can too.

Just read the part about NMDA receptors and dynorphin-holy crap. This isn’t just medical, it’s neuroscience poetry. The body’s trying to protect itself, but the drugs hijack the alarm system. We’re not broken. We’re overstimulated.

Wow. Just… wow. I’ve been on oxycodone for 4 years for fibro, and my skin hurts when my partner brushes past me? I thought I was going crazy. This is the first time someone explained it without making me feel like a junkie. Thank you. I’m printing this out and taking it to my doctor tomorrow. Please, someone tell me I’m not alone.

Another anti-opioid propaganda piece. They just want you off the meds so they can sell you yoga and crystals. Your pain is real. Stop listening to these pseudoscience gurus

Phil Hillson you’re literally the reason people die. Shut the hell up. This isn’t about crystals-it’s about neurobiology. I was misdiagnosed for 3 years because doctors thought I was ‘drug seeking.’ I had OIH. Now I’m on buprenorphine and I can hold my kid without crying. You don’t get to dismiss this because you’re scared of change.

Is it possible that OIH is just the final stage of a broken system? We treat pain like a broken pipe-turn up the pressure. But the body isn’t plumbing. It’s a living, adaptive, screaming organism. Maybe the real problem isn’t opioids-it’s that we refuse to listen to what pain is trying to say.

Mark my words: this is a pharmaceutical trap. They invented OIH so they could sell you ketamine infusions at $2,000 a pop. The real solution? Stop taking pills. Go live in the mountains. Breathe. Meditate. The body heals itself when the mind stops screaming.

lol so if i take less opiates my pain goes away?? what a shocker. i thought it was my spine, turns out its my brain being dumb. also who even uses the OIHQ? sounds like a survey from a walmart focus group

To the person who said ‘go live in the mountains’-I’m a single mom with neuropathy and two kids. I don’t have time to meditate for 8 hours a day. But I do have time to read science. This isn’t about spirituality. It’s about physiology. Thank you, author, for writing this without shame. We need more of this.

According to the American Academy of Pain Medicine’s 2023 position statement on neuroplastic pain syndromes, opioid-induced hyperalgesia is classified as a central sensitization disorder with a Class IIb evidence rating. The OIHQ demonstrates a sensitivity of 0.85 and specificity of 0.79 in validation cohorts. The tapering protocols recommended herein align with guidelines from the CDC and NCCN, though individualized dosing is advised due to pharmacogenetic variability in CYP2D6 and COMT polymorphisms.

I’ve been a pain specialist for 22 years. I used to prescribe opioids freely. Then I saw patients get worse. Not because they were addicted. Because their nervous systems were rewired. I’ve watched people cry because they thought they were weak. They weren’t. They were victims of a system that didn’t understand biology. This article? It’s not just correct. It’s necessary.