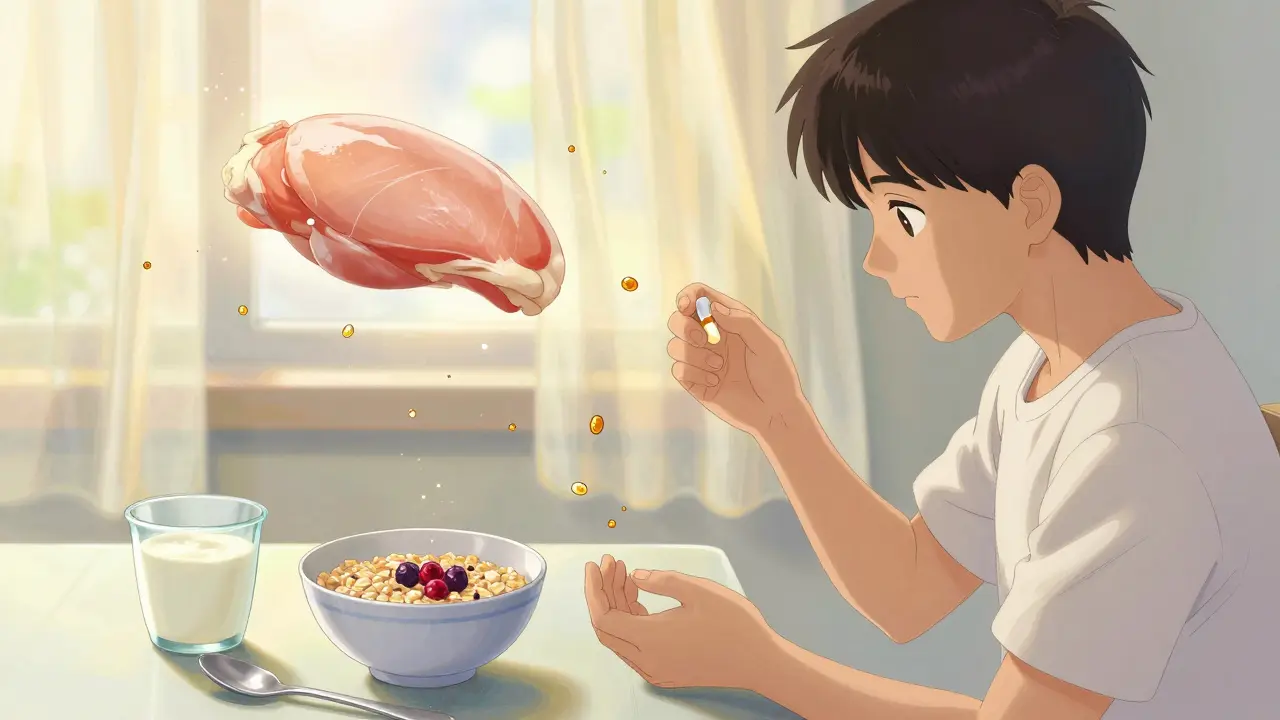

Many people don’t realize that what they eat for breakfast can make their morning medication less effective. If you’re taking drugs like levodopa for Parkinson’s, or certain antibiotics, the protein in your eggs, yogurt, or chicken breast might be blocking your body from absorbing them properly. This isn’t just a theory-it’s a well-documented, clinically significant issue that affects thousands of people every day. And it’s not about eating too much protein. It’s about when you eat it.

How Protein Blocks Medication Absorption

Protein-rich foods don’t just fill you up-they trigger a biological competition inside your gut and brain. When you eat meat, beans, dairy, or even a protein shake, your body breaks down the protein into amino acids. These amino acids then flood your bloodstream, especially large neutral ones like leucine, isoleucine, and tyrosine.

Here’s the problem: the same transporters in your gut and blood-brain barrier that move these amino acids also carry certain medications. Levodopa, the main drug used to treat Parkinson’s disease, is one of them. It needs those transporters to get into your brain. But if there are too many amino acids around-say, from a high-protein meal-levodopa gets pushed out of line. Studies show this can cut levodopa absorption by 30% to 50% in about 60% of patients. That means your medication isn’t working as well, and your tremors, stiffness, or slowness might come back sooner.

It’s not just levodopa. Other drugs like some epilepsy medications (phenytoin, gabapentin) and certain antibiotics (penicillin, amoxicillin) also rely on these transporters. Protein can reduce their absorption by 15% to 20%. Meanwhile, other drugs, like some cholesterol-lowering statins, are affected more by fiber than protein. So the issue isn’t universal-but for specific medications, it’s huge.

Why Protein Is Different from Fat or Fiber

You’ve probably heard that fatty meals can slow down how fast your body absorbs pills. That’s true. High-fat meals delay stomach emptying by 60 to 90 minutes. But protein does something more complex. It doesn’t just slow things down-it actively competes.

While fat mainly affects timing, protein changes the actual amount of drug that gets absorbed. Research from the NIH (PMC8747252) shows that after a high-protein meal, amino acid levels in the blood spike by 200% to 300% within 30 minutes. That’s enough to overwhelm the transporters. At the same time, protein increases blood flow to the intestines by 25% to 30%, which can actually help some drugs absorb better. This dual effect makes protein interactions harder to predict than fat or fiber.

That’s why the FDA started requiring food-effect studies for all new drugs in 2019. They now test drugs with both low-fat and high-fat meals, but protein-rich meals are becoming a standard part of those tests. In fact, 42% of oral drugs show some kind of food interaction, and protein-containing meals are the biggest source of variability for 18% of them.

The Levodopa Example: A Real-World Crisis

Levodopa is the most studied case. It’s the gold standard for Parkinson’s treatment. But for many patients, it stops working as well after meals. A 2023 Parkinson’s Foundation report found that patients who took levodopa with lunch or dinner had up to 45% less brain uptake than when they took it on an empty stomach.

The result? More ‘off’ time-periods when symptoms return because the drug isn’t working. One patient tracked on a wearable sensor saw their ‘off’ time drop from 5.2 hours to just 2.1 hours after switching to a protein-redistribution diet. That’s not a small change. It’s the difference between being able to walk across the room or needing help.

Here’s what experts recommend: take levodopa 30 to 60 minutes before meals that contain more than 15 grams of protein. A typical chicken breast has about 30g. A cup of lentils? 18g. Even a protein bar can have 7g or more. That’s enough to interfere.

And here’s the twist: you don’t need to cut protein out of your diet. In fact, doing that can be dangerous. A 2024 study in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease found that 23% of patients on strict low-protein diets developed muscle wasting within 18 months. That’s not a trade-off worth making.

The Protein Redistribution Strategy

The real solution? Shift your protein intake. Instead of spreading protein evenly across meals, save most of it for dinner.

The Parkinson’s Foundation recommends consuming 70% of your daily protein at your evening meal. That means keeping breakfast and lunch light-around 10 to 15g per meal-and letting dinner carry the load. For example:

- Breakfast: Oatmeal with berries (3g protein)

- Lunch: Salad with a small portion of tofu (12g protein)

- Dinner: Salmon, quinoa, and roasted veggies (50g protein)

This way, your levodopa has a clear window to work during the day when you need it most. Clinical trials from the Michael J. Fox Foundation show this approach increases ‘on’ time by an average of 2.5 hours per day. That’s more than half a day of better movement.

And it works. A 2023 study from the University of Florida found that 85% of patients stuck with this plan after three months-especially when they worked with a dietitian. Apps like ProteinTracker for PD (developed by Johns Hopkins) help people log meals and get alerts when protein levels are too high around medication time. Users report 40% fewer timing mistakes.

What About Other Medications?

Levodopa gets the most attention, but it’s not alone. Antibiotics like penicillin and amoxicillin can also be affected. If you take them with a protein-heavy meal, you might not get the full dose. That could mean the infection doesn’t clear, or worse-it develops resistance.

Some thyroid medications (like levothyroxine) are sensitive to calcium and iron, but protein can also interfere slightly. The same goes for bisphosphonates used for osteoporosis. Always check the label. If it says ‘take on an empty stomach,’ that’s a red flag.

Drugs are classified by how they behave in the body using the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). Class I drugs (like ibuprofen) are barely affected by food. Class III drugs (like levodopa) are highly sensitive. If your drug is in Class III, protein timing matters.

Why Doctors Don’t Always Talk About This

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most doctors don’t bring this up. A 2024 position paper from the American Society for Nutrition found that 68% of clinicians never discuss protein timing with patients starting levodopa. Even neurologists who specialize in movement disorders often skip it.

Dr. Alberto Espay, a leading Parkinson’s expert, says the protein-redistribution diet has strong evidence but remains underused. The European Medicines Agency found that 61% of medication guides don’t even mention protein interactions. The FDA’s 2025 draft guidance is trying to fix that by pushing for standardized warning labels-like those for alcohol or grapefruit.

Patients are ahead of the system. On forums like the Parkinson’s Foundation website, 68% of users say they take their medication before meals because they figured it out on their own. One Reddit user wrote: ‘I didn’t know why my meds stopped working after lunch-until I started tracking my protein. Game changer.’

Practical Tips for Managing Protein and Medication

If you’re taking a medication that might interact with protein, here’s what to do:

- Check your drug label. Look for phrases like ‘take on an empty stomach’ or ‘avoid high-protein meals.’

- Time your doses. Take medication 30 to 60 minutes before meals. If nausea is a problem, try a low-protein snack (under 5g) like a banana or apple.

- Track your protein. Use an app or food diary. Remember: 1 egg = 6g, 1 cup yogurt = 10g, 1 slice of bread = 3-5g.

- Redistribute your protein. Save the big protein meals for dinner. Keep breakfast and lunch light.

- Ask for help. Talk to a registered dietitian who specializes in medication interactions. Most insurance covers this.

And don’t forget: hidden protein is everywhere. Granola bars, protein-fortified cereals, protein shakes, and even some ‘healthy’ soups can contain 7g or more. Read labels. Your medication’s effectiveness depends on it.

The Future: Better Labels, Better Tools

Change is coming. Pharmaceutical companies now run food-effect studies in 92% of Phase III trials, up from 67% in 2020. The FDA is pushing for a ‘Protein Interaction Score’ on drug labels-similar to how alcohol warnings appear. By 2030, personalized algorithms could cut therapeutic failures by 45%.

Emerging research is even more promising. A March 2025 study in Nature Medicine found that certain probiotics reduced protein competition for drug transporters by 25%. Time-restricted eating (eating protein only between noon and 8 p.m.) improved levodopa effectiveness by 32% in 78% of participants.

And for those who still struggle? Drugs like Duopa-levodopa delivered directly into the small intestine via a pump-bypass the gut entirely. Medicare data shows over 12,000 new users each year. It’s not for everyone, but for some, it’s life-changing.

At the end of the day, this isn’t about being perfect. It’s about awareness. You don’t need to become a nutritionist. You just need to know that your protein-packed lunch might be undoing your morning pill. And that’s something you can change-today.

Bro, I just realized my levodopa was useless because I was eating peanut butter toast before my pill 🤯. I switched to banana + meds, and my tremors? Gone for hours. Game. Changer. 🍌💊

omg i had no idea!! i was taking my meds with my protein shake like a total dumbass 😭 switched to just oatmeal in the am and now i can actually walk to my car without falling over. thank u for this post!!

This is a critically important topic that remains under-addressed in clinical practice. The biochemical mechanisms underlying amino acid competition at the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT1) are well-documented, yet patient education remains inconsistent. Standardized dietary counseling, particularly for Class III BCS medications, should be integrated into routine care pathways. Multidisciplinary collaboration between neurologists and registered dietitians is not merely beneficial-it is ethically imperative.

So let me get this straight-doctors are STILL letting people eat protein with their meds like it’s a free-for-all?!?!?!!? I mean, c’mon. We have peer-reviewed studies, FDA guidelines, and actual wearable sensor data-and yet? Nada. Zero. Zip. They’d rather slap on a ‘take with food’ label than actually tell you your bacon-and-eggs breakfast is sabotaging your brain. This isn’t negligence-it’s malpractice with a side of coffee. #ProteinIsTheEnemy

This is all a lie. Big Pharma and the protein industry are working together to make you think protein is bad. They want you to eat only carbs so they can sell you more drugs. The real cause of your symptoms? 5G radiation + glyphosate in your tofu. Read the FDA draft guidance-there’s a hidden clause about mandatory protein suppression. I’ve seen the documents. They’re deleting this from the internet.

I’ve been doing the protein redistribution thing for 8 months now and honestly it’s been the most life-changing thing since my diagnosis. Dinner’s my protein feast. Breakfast? Just fruit. Lunch? A bit of cheese. No drama. No panic. Just better movement. And yeah I know it’s not perfect but it’s way better than what I was doing before

The clinical evidence supporting protein redistribution in Parkinson’s disease is robust and reproducible. However, implementation remains suboptimal due to patient adherence challenges and lack of standardized dietary protocols. Future interventions should incorporate digital tools, such as real-time nutrient tracking integrated with electronic health records, to facilitate precision timing of medication administration.

i started doing the protein shift last month and now i can tie my shoes without help. no joke. i eat like 2 eggs for breakfast and save my chicken for dinner. it’s so simple but it feels like a miracle. also-i use the ProteinTracker app and it sends me a little ding when i’m about to eat protein near my meds. i love it. you got this. 💪