QT Prolongation Risk Calculator

Assess Torsades de Pointes Risk

This tool evaluates risk factors based on clinical data from the article. Use for patients starting QT-prolonging medications.

Torsades de Pointes isn’t something you hear about every day-but when it happens, it can kill in seconds. It’s a dangerous heart rhythm triggered by certain medications that stretch out the heart’s electrical recovery time, measured as the QT interval on an ECG. This isn’t a rare glitch-it’s a well-documented, preventable death sentence that quietly claims lives every year, often without warning. The good news? If you know what to look for, you can stop it before it starts.

What Exactly Is Torsades de Pointes?

Torsades de Pointes (TdP) is a type of irregular heartbeat that looks like the QRS complexes on an ECG are twisting around the baseline-hence the French name, meaning "twisting of the points." It doesn’t come out of nowhere. It only happens when the heart’s repolarization phase is delayed, which shows up as a prolonged QT interval. A QTc (corrected QT interval) over 500 milliseconds doubles or triples your risk. For men, anything above 450 ms is considered prolonged; for women, it’s 460 ms. But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. The real danger kicks in when that prolonged interval triggers early afterdepolarizations-abnormal electrical sparks in the heart muscle that set off this chaotic rhythm.Which Medications Cause It?

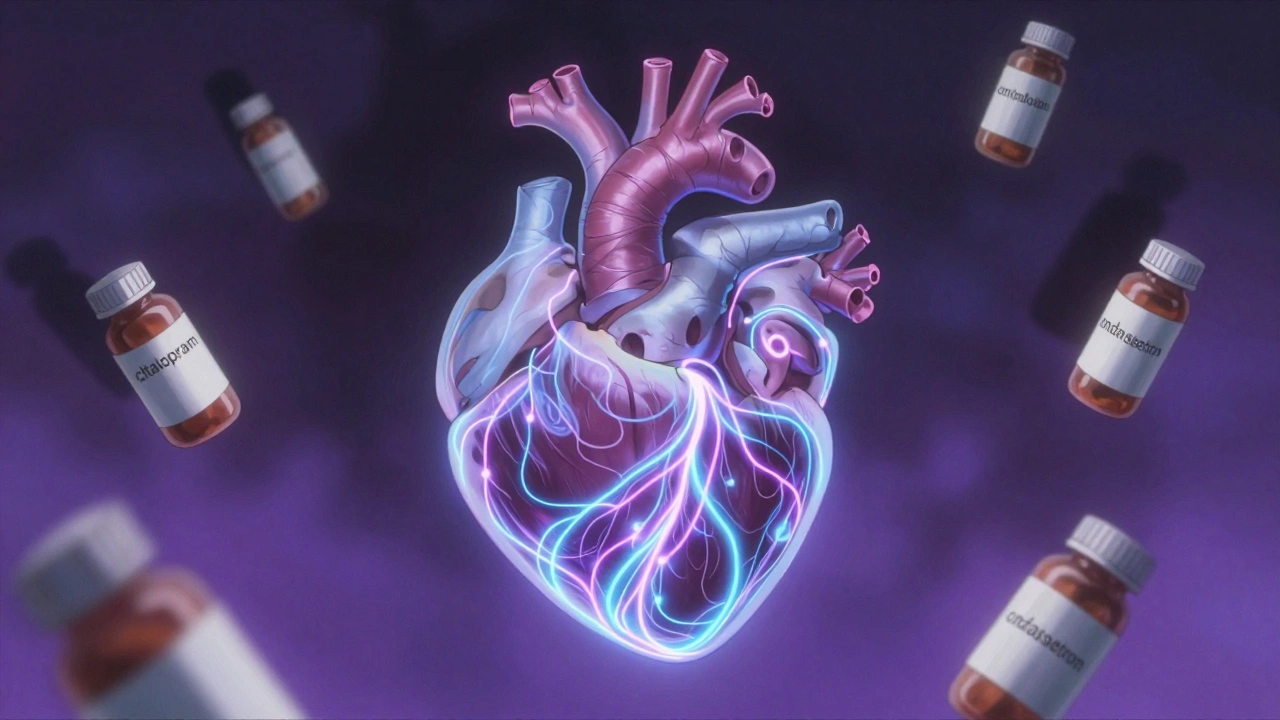

Over 200 commonly used drugs can lengthen the QT interval. Some are obvious culprits, like antiarrhythmics (quinidine, sotalol, dofetilide), but many are everyday prescriptions you’d never suspect. Antidepressants like citalopram and escitalopram-especially at doses above 40 mg/day-carry clear risk. Antipsychotics such as haloperidol and ziprasidone? High risk. Antibiotics like clarithromycin and moxifloxacin? Yes. Even anti-nausea drugs like ondansetron (especially IV doses over 16 mg) and the opioid methadone (when doses go above 100 mg/day) can trigger it. The CredibleMeds database classifies these drugs into three tiers: "Known Risk," "Possible Risk," and "Conditional Risk." The "Known Risk" list includes drugs with clear, documented cases of TdP. That’s where you need to pause. And here’s the twist: some of the most dangerous drugs are the ones meant to treat heart rhythm problems. That’s because they directly interfere with the hERG potassium channel-the same channel that keeps the heart’s electrical cycle on schedule. Block that channel, and repolarization stalls. The heart can’t reset fast enough. That’s when TdP starts.Who’s Most at Risk?

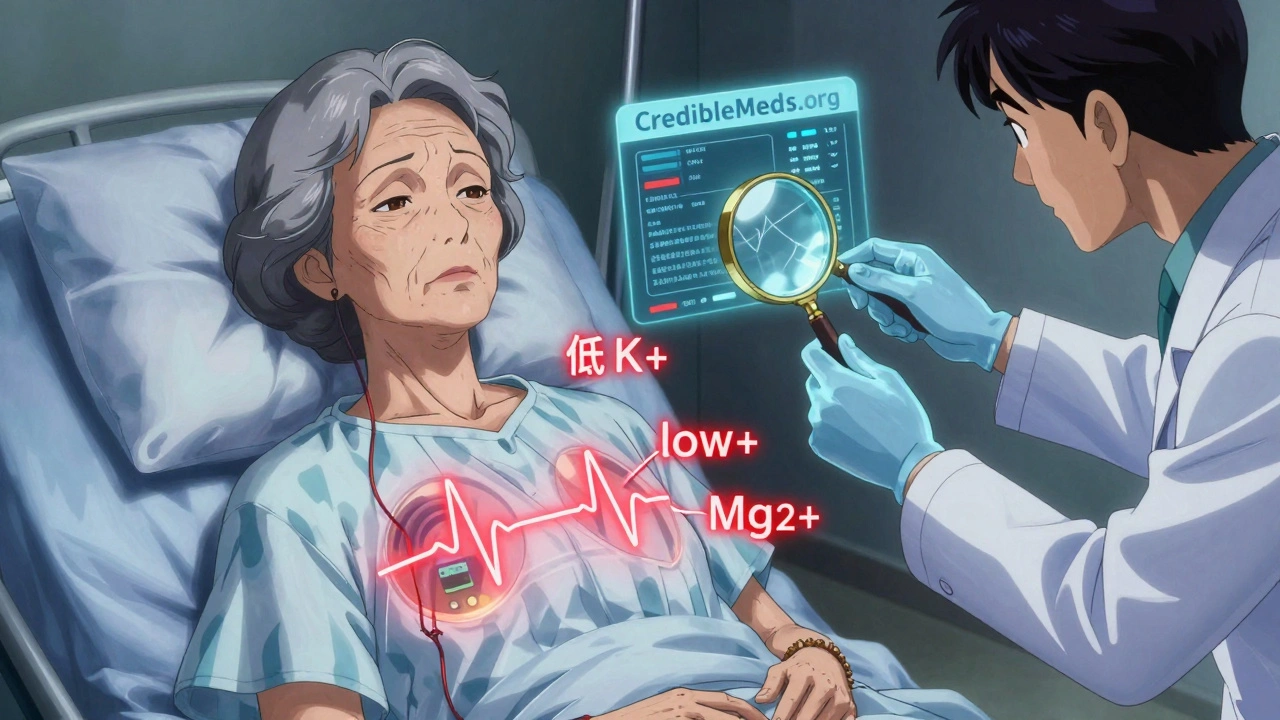

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. Women make up 70% of TdP cases-even though both genders experience similar QT prolongation. People over 65 account for nearly 7 out of 10 cases. And it’s not just age or gender. Half the time, there’s a hidden factor making things worse. Low potassium (hypokalemia) is present in 43% of cases. Low magnesium (hypomagnesemia) shows up in 31%. Both are easy to fix-if you check. A potassium level below 3.5 mmol/L increases risk by over 3 times. Magnesium under 1.6 mg/dL raises it by nearly 3 times too. Bradycardia (heart rate under 60 bpm) is in 57% of cases. Heart failure, kidney disease, liver disease, and taking more than one QT-prolonging drug at once? Each adds another layer of danger. If you’re on methadone and have low potassium and are over 70? Your risk isn’t just elevated-it’s critical.

How to Prevent It Before It Starts

Prevention isn’t complicated. It’s systematic. And it starts before the first pill is taken.- Check the baseline ECG. Always get a baseline QTc before starting a high-risk drug. Don’t skip this-even if the patient feels fine.

- Review every medication. Use CredibleMeds.org. If a patient is on two or more drugs on the "Known Risk" list, reconsider the combination. Even one "Known" and one "Conditional" can be enough to tip the scale.

- Fix electrolytes first. If potassium is under 4.0 mmol/L or magnesium under 2.0 mg/dL, correct them before prescribing. No exceptions.

- Know the dosing limits. Citalopram? Max 40 mg/day. In patients over 60? Stick to 20 mg. Ondansetron IV? Don’t exceed 16 mg. Methadone above 100 mg/day? Mandatory ECG monitoring.

- Watch for drug interactions. Clarithromycin and statins? Watch out. Many QT-prolonging drugs are metabolized by CYP3A4. If another drug blocks that pathway (like ketoconazole or grapefruit juice), levels spike. Risk jumps by 63%.

What to Do If TdP Happens

If you see TdP on the monitor, time is everything. The rhythm can self-correct-but it can also turn into ventricular fibrillation and kill within minutes.- Give magnesium sulfate immediately. 1 to 2 grams IV. It works in 82% of cases-even if magnesium levels are normal. It stabilizes the heart’s electrical activity.

- Pace the heart. Temporary pacing to keep the heart rate above 90 bpm shortens the QT interval and stops the arrhythmia. It’s successful in 76% of cases.

- Correct electrolytes. Recheck potassium and magnesium. Keep potassium above 4.5 mmol/L until the risk passes.

- Use isoproterenol if pacing isn’t available. It increases heart rate and shortens repolarization. But it’s a second-line option.

- Stop the offending drug. Immediately. No waiting. No "let’s see how it goes."

What’s Changing in 2025?

The rules are getting smarter. The FDA no longer demands blanket avoidance of QT-prolonging drugs. Instead, they want smart risk assessment. New tools like concentration-QTc modeling let drug makers predict risk without full-scale trials, cutting development time by months. Machine learning models from Mayo Clinic now predict individual TdP risk with 89% accuracy by combining 17 factors-age, gender, kidney function, drug combinations, electrolytes, and more. The TENTACLE registry, tracking 15,000 patients, is refining the red flags. Early data suggests that a QTc over 520 ms, with a change of more than 70 ms from baseline, means a 94% chance of TdP. That’s not a gray zone-it’s a clear warning sign. And legislation is catching up. The 2022 PREVENT TdP Act, still under review, would standardize ECG monitoring protocols across hospitals. If passed, it could prevent 200 deaths a year.Don’t Panic-But Don’t Ignore It

The absolute risk of TdP is still low: about 4 cases per million women each year. But that’s not a reason to shrug. For the person who gets it, the risk is 100%. And unlike many drug reactions, this one is almost entirely preventable. The biggest mistake? Assuming "it won’t happen to my patient." It happens to people on common prescriptions, with common conditions, and common lab values that were never checked. It happens because no one connected the dots. The solution isn’t avoiding life-saving drugs. It’s knowing which ones are dangerous, who’s vulnerable, and how to monitor properly. A simple ECG. A blood test for potassium. A quick check of the drug list. That’s all it takes to stop TdP before it starts.Can Torsades de Pointes happen with over-the-counter drugs?

Yes. While most cases come from prescription drugs, some OTC medications carry risk. Antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and certain herbal supplements like licorice root can prolong the QT interval, especially in high doses or when combined with other risk factors. People taking multiple medications-prescription or not-should always review their full list with a doctor or pharmacist.

Is a prolonged QT interval always dangerous?

No. A slightly prolonged QT interval (450-480 ms) in a healthy person without other risk factors is usually not dangerous. But once QTc exceeds 500 ms, or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline, the risk of TdP rises sharply. The danger isn’t just the number-it’s the combination of factors: age, gender, electrolytes, other drugs, and heart health.

Can TdP happen in people with no heart disease?

Absolutely. Many cases occur in people with otherwise healthy hearts. The trigger is often a combination of medication and electrolyte imbalance-not structural heart disease. A 68-year-old woman on citalopram and a diuretic, with low potassium, can develop TdP even if her echocardiogram is perfect.

How often should QTc be checked after starting a high-risk drug?

For drugs like methadone, sotalol, or dofetilide, check the ECG at baseline, then 2-5 days after starting or after each dose increase. For others like citalopram or ondansetron, a single baseline ECG is usually enough if no other risk factors are present. If any risk factors exist, repeat the ECG within one week. Monitoring frequency should be tailored to the drug and the patient’s risk profile.

Are there any safe alternatives to QT-prolonging drugs?

Yes, often. For nausea, ondansetron can be replaced with metoclopramide (lower QT risk). For depression, escitalopram might be switched to sertraline or citalopram at a lower dose. For infection, azithromycin (lower risk) can replace clarithromycin. Always check CredibleMeds.org for alternatives. The goal isn’t to avoid treatment-it’s to choose the safest option for that individual.

Just read this and immediately checked my last ECG. Glad mine was normal. This is the kind of stuff every med student should memorize before residency.

In India, we often prescribe citalopram without checking QTc. This article is a wake-up call. Electrolytes first, always.

omg i had ondansetron last month and didnt even know it could do this. thanks for the heads up!!

It's not just the drugs... it's the system. We're trained to prescribe, not to pause. The hERG channel doesn't care about your EHR workflow. The heart doesn't care about your 12-minute visit. And yet, we're expected to prevent death with a clipboard and a checklist. The tragedy isn't the arrhythmia-it's the institutional blindness.

Why do we still treat cardiac risk like an afterthought? Because it's easier to write a script than to question a protocol. Because billing codes don't include 'double-check potassium.' Because we're all just trying to get through the day without another charting error.

And now, someone's mother is dead because her QTc was 512, and no one looked. Again.

It's not negligence. It's normalization.

We don't need more guidelines. We need to stop pretending we're following the ones we already have.

Every time you skip the ECG because 'she's fine,' you're gambling with a heartbeat.

And the worst part? You'll never know you lost.

Wait-so grapefruit juice + clarithromycin + statin = QT prolongation? I had this combo last winter. My cardiologist never mentioned it. Should I be worried?

Yes. You should be concerned. Even if you're asymptomatic, that combo is a known risk triad. Get a repeat ECG and check your electrolytes. Don’t wait for symptoms. TdP doesn’t warn you.

The CredibleMeds database is underutilized in clinical practice. I’ve seen residents ignore it because ‘it’s too much work.’ But it’s literally a free, evidence-based safety net. Use it.

This is why America’s healthcare is broken. We let algorithms and checklists replace judgment. We don’t teach critical thinking anymore. We just tell doctors to ‘follow the protocol.’ But protocols don’t think. People do. And if you’re not thinking, you’re killing people.

im not a doc but i read this and my brain hurt in a good way. like… wow. this is real. and nobody talks about it.

As a board-certified cardiologist, I must say this article is fundamentally flawed. The FDA’s stance on concentration-QTc modeling is not yet standard of care, and citing the TENTACLE registry without peer-reviewed publication is irresponsible. Also, ‘methadone above 100 mg’ is misleading-it’s not the dose, it’s the trough level.

They’re hiding something. Why is no one talking about the pharmaceutical companies funding the ‘safe’ alternatives? Who profits when we switch from azithromycin to clarithromycin? Who gets paid when we order 3 ECGs a week? This isn’t medicine-it’s a money machine. And we’re all just pawns.

Just shared this with my whole team. 🙌 We’re starting mandatory QT checks before any new psych med now. Also, magnesium IVs are now on our crash cart checklist. Thank you for this. ❤️

So basically if you’re a woman over 65 on antidepressants with low potassium you’re basically a walking time bomb and no one cares

I’ve been teaching this to my residents for years, but I’ll be honest-it’s hard to get buy-in. Nurses don’t always push back when an order comes in. Pharmacists are overwhelmed. Patients don’t know to ask. It takes a village, but most hospitals don’t even have a village-they have a spreadsheet and a hope. I wish more people understood that preventing TdP isn’t about being perfect. It’s about being consistent. One ECG. One potassium check. One drug interaction review. That’s it. You don’t need a genius. You just need to not skip the steps.

And if you’re reading this and you’re a provider? Don’t wait for a code to happen before you change your habits. The next patient could be your sibling. Or your parent. Or you.

Don’t let ‘I didn’t know’ be your excuse. The knowledge is out there. It’s free. It’s published. It’s in your EHR.

What’s stopping you?

My grandma almost died from this. She was on citalopram and furosemide. No one checked her labs. She collapsed in the kitchen. We got lucky. Please, if you’re on meds like this-get your numbers checked. It’s just a blood test. It takes five minutes. It could save your life.