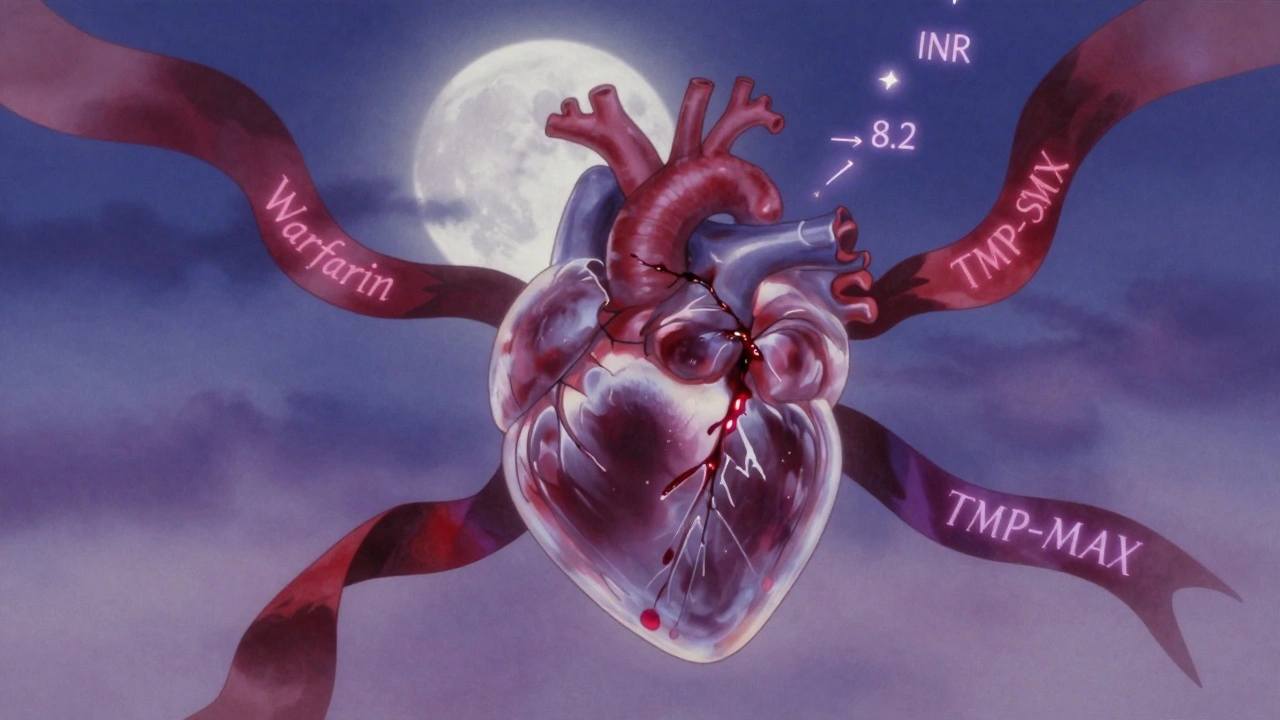

Warfarin Antibiotic Interaction: What You Need to Know About Dangerous Drug Combos

When you take warfarin, a blood thinner used to prevent clots in people with atrial fibrillation, artificial heart valves, or deep vein thrombosis. Also known as Coumadin, it works by blocking vitamin K, which your body needs to form clots. But when you add certain antibiotics, medications that kill or slow bacteria, they can interfere with how warfarin is broken down—sending your INR levels skyrocketing and raising your risk of dangerous bleeding.

This isn’t rare. Studies show that up to 1 in 5 people on warfarin who start an antibiotic see their INR rise by 2 points or more within days. Some antibiotics like trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) and ciprofloxacin (Cipro) are especially risky—they block the liver enzymes that clear warfarin from your blood. Even metronidazole (Flagyl), often used for gut or dental infections, can turn a stable dose into a medical emergency. On the flip side, some antibiotics like amoxicillin or azithromycin are safer choices, but only if your doctor checks your INR first. The problem? Many patients don’t know their antibiotic could be as dangerous as skipping a dose of warfarin. That’s why every time you get a new prescription, you need to ask: "Will this interact with my blood thinner?"

It’s not just about the drug itself—it’s about your body’s response. Your liver, kidneys, gut bacteria, and even what you eat all play a role. A change in diet—like suddenly eating more kale or spinach—can also throw off your INR. Combine that with an antibiotic that alters your gut flora or liver function, and you’ve got a perfect storm. That’s why regular INR tests aren’t optional when you’re on warfarin and antibiotics. If you’re heading to the ER for a cough or infection, make sure your meds list includes warfarin. Don’t assume the doctor knows. Don’t assume the pharmacist checked. Your life depends on it.

Below, you’ll find real-world guides on how to spot dangerous drug combos, what to do when your meds don’t mix, and how to protect yourself from side effects that no one warned you about. These aren’t theoretical risks—they’re the kind of mistakes that land people in the hospital. And you don’t have to be one of them.